Bottlenecks to resolving chronic pain

What if you're working on the wrong bottleneck?

Most people with chronic pain aren’t stuck because their pain is mysterious — they’re stuck because they’re working on the wrong bottleneck.

This map of bottlenecks comes from years of self-experimentation, and the dozens of people I’ve since helped. It is not medical advice.

Note: This applies to chronic pain where the central nervous system is heavily involved. It doesn’t cover the minority of cases driven by clear local injury — like tumors pressing on nerves, broken bones, or other obvious tissue damage1.

Starting out

Before seriously attempting any work, there are three common bottlenecks I’ve observed.

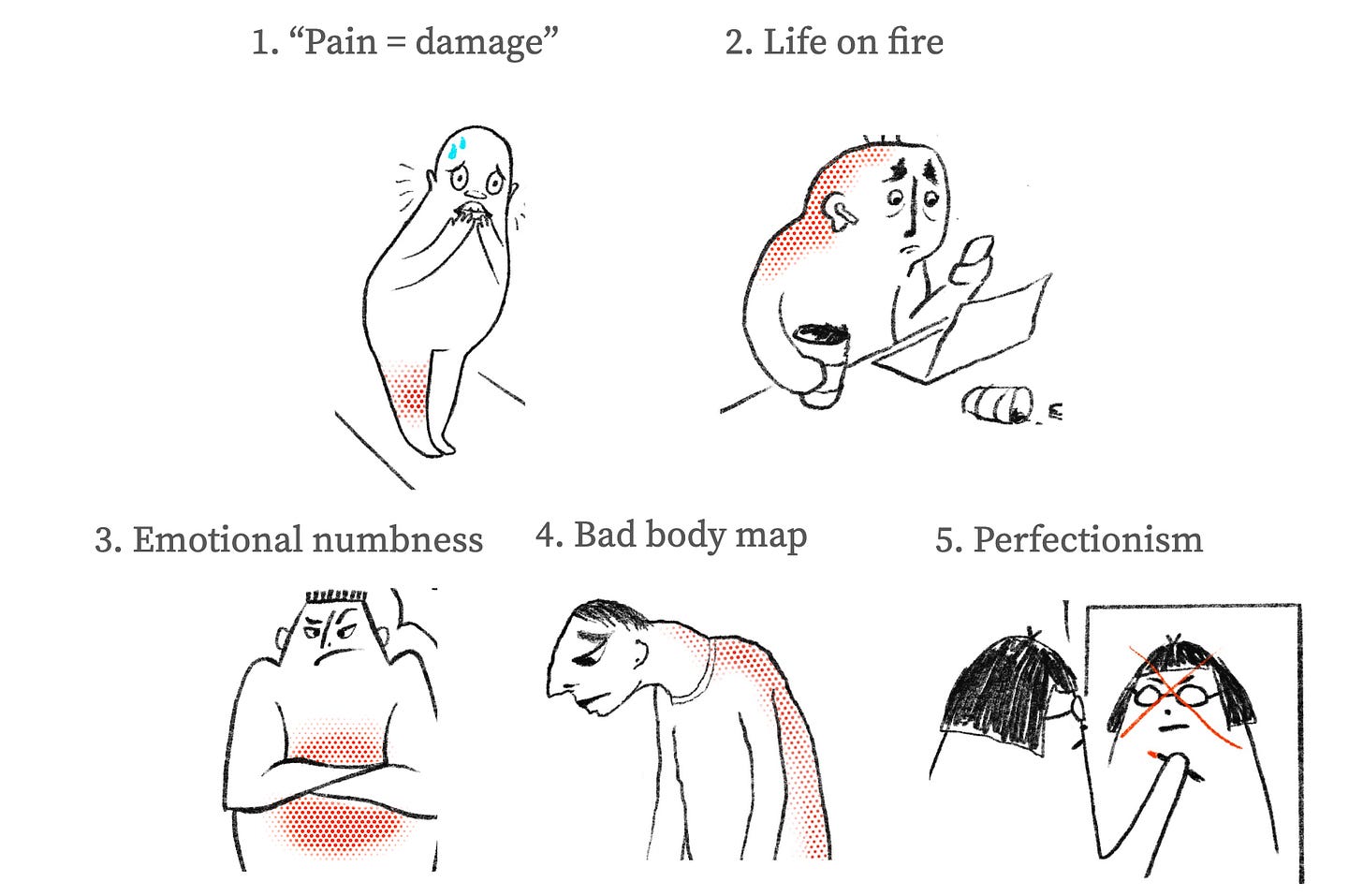

Belief that pain = damage

If you believe chronic pain is just a sign of tissue damage, you won’t look closely at your inner experience. You won’t notice how pain can be learned, how it is heavily tied to your emotions, and how — if you look close enough — it is generated by your nervous system.

Most people I meet with chronic pain are stuck here. They focus on biomechanical fixes — painkillers, surgery, physical therapy. When they work, the pain may still linger in the background as a dull drag on your experience, or it may transfer to different parts of your body.

Life on fire

When you are overworked, dealing with other health issues, or worrying about how you’ll pay rent next month, you won’t have the slack needed to engage in the process.

Often people will see that their emotional state heavily influences their pain, but do not actually make the slack needed for deep change.

Processing

Once people make space to do the work, there are still a few common bottlenecks they might face.

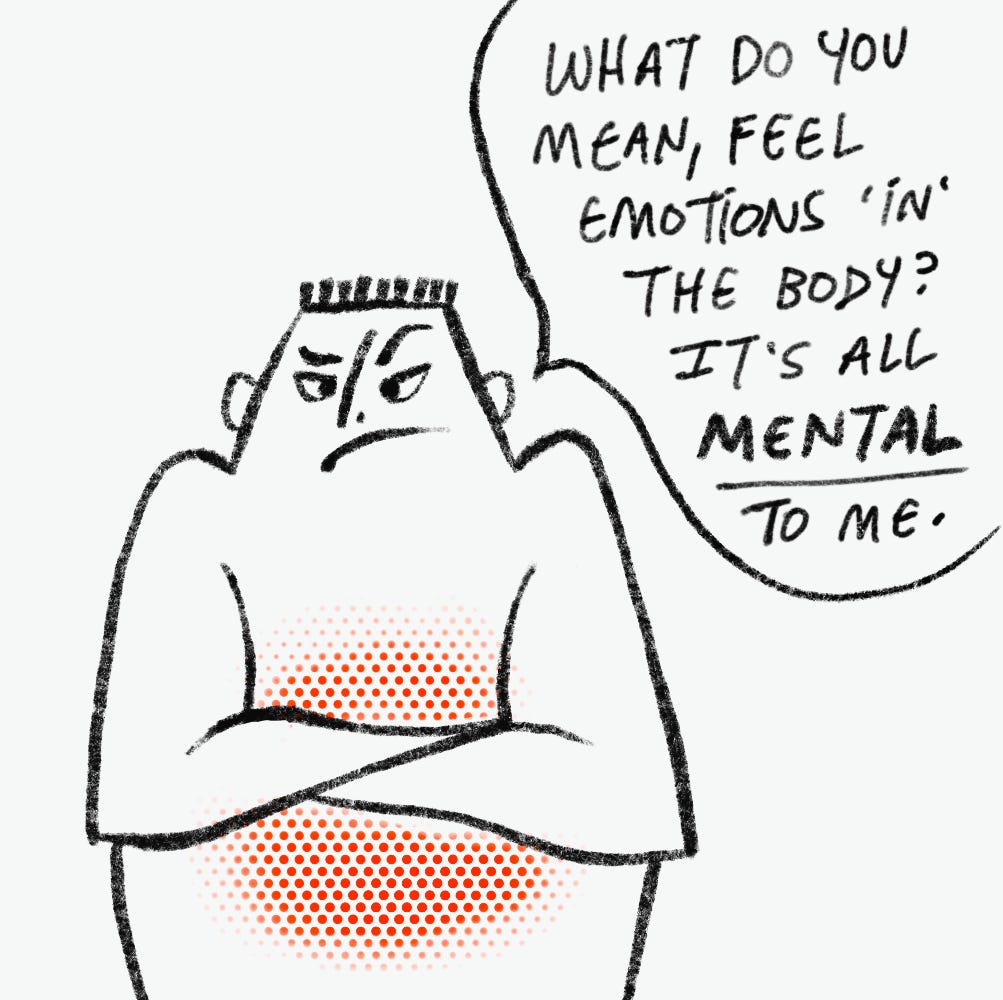

Poor emotional attuning

Much like recognizing a piano chord, sensing emotions is a skill that can be learned.

Often this skill is largely absent in people with pain. Symptoms of this include: emotions feel highly conceptual (felt ‘in the head’, or similar to thoughts), your chest or midsection feels like one vague blob “my body just feels tension when I’m anxious — it’s hard to be more specific”.

Example of clearly described interoception: “anxiety shows up as this band of tightness especially around the top of my left diaphragm. I notice the back of my right neck is also tight especially as I breathe and there’s definitely some fear there too”

If you can’t clearly feel an emotion in your body, the underlying emotional beliefs tend to remain stuck below conscious awareness — and the mind keeps looping in a catastrophizing cycle.

Bad body map

Imagine keeping your hands in thick gloves for five years, and one day taking them off to play the violin. Your fingers might be strong, but they’d feel clumsy. You’d struggle to sense each individual string and apply way more force than is needed.

Something similar often happens with chronic pain.

The pain is coupled with poor sensorimotor discernment. Because you can’t sense that the mid-low back tenses unnecessarily hard every time you stand up, you can’t let it go, and a day full of sitting and standing has your left lower back feeling sore2.

Self-attacking perfectionism

Imagine that the next presentation you give is going to determine whether you succeed or fail for the rest of your life. Everything, all your dreams and wishes, your family’s hopes, all hinge on how good the presentation is. As you walk up, with your slides prepared, what would it feel like? How easily could you breathe? How much could you sense your whole body? Now what if this were true for every presentation for the rest of your life?

Having very high personal standards is often linked with self-punishment and catastrophizing. The stakes feel very high, and the intensity of focus leads to a tension to ‘do everything right’. This is paradoxically the opposite of the internal movement of accepting and relaxing — the ‘unlearning’ of self-tension.

Integrating

Even as interoception improves and self-acceptance grows, there may still be situations that feel awkward. Part of developing the better body map also means learning to move with ease.

At this stage, there is a baseline comfort — still, some situations reliably trigger pain. Family gatherings, performance reviews — these can all be worked with.

Lack of progress is often due to working on the wrong bottleneck

Early on, Tanner and I took on people who were excited to work with us, but who seemed to be mysteriously stuck. On closer examination, they weren’t doing any of the practices in between sessions and seemed to be generally overwhelmed, even as there would be progress during the sessions.

For a while we thought it reflected our lack of skill or clarity in explanation. After seeing the same approach work very rapidly for others, it’s made more sense to see that certain clients were bottlenecked on the pre-requisites, which we had little ability to affect.

Bottlenecks are not stages of progression

Although I’ve ordered it roughly chronologically from what I’ve observed, pain is the output of a complex system. You do not need to ‘complete’ one bottleneck to advance to the next. Since our sensations are heavily bundled with our thoughts and emotions, working deeply with one bottleneck can often unravel and resolve many others. Many people find rapid resolution once they meet the prerequisites.

Pain is workable

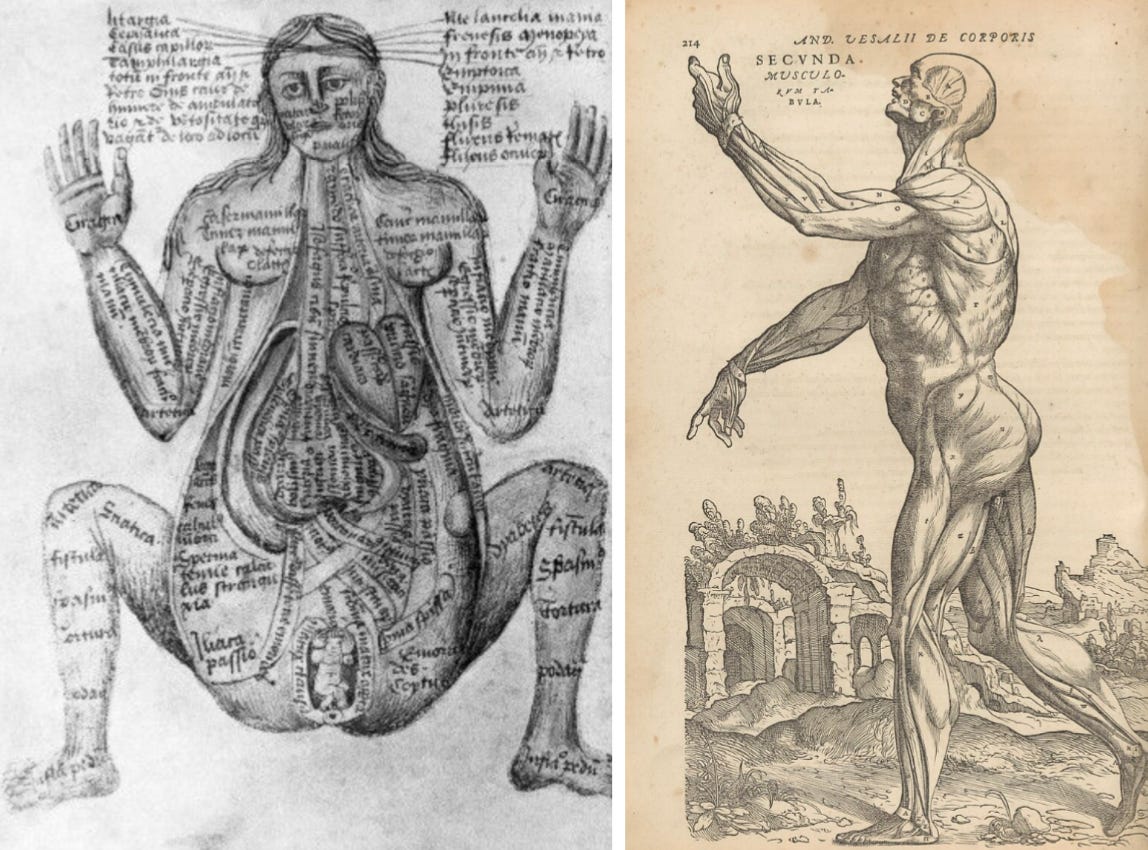

The father of modern human anatomy, Andreas Vesalius, made the first clear map of the human body. Above, you can see an example of how the human body was illustrated prior to Vesalius. Our conceptual tools begin as blurry, gross things that become refined over time.

Vesalius’ maps were brilliant innovations at an external map of the human body. I’m interested in internal, subjective maps of human experience3.

What I’ve illustrated here is vague, impressionistic. Yet I’m convinced it’s clear enough to be directly helpful for making progress on chronic pain.

Pain is complex, but noticing these patterns gives me the conviction that most people with chronic pain can experience lasting relief. In many cases, this relief can take much less time.

Thank you to Chris Lakin for inspiring the ‘bottlenecks’ framing. Also to Orpheas, Agi, Misha for feedback, and to Olivia for the illustrations.

For more on this, see our evidence page.

Thomas Hanna (popularizer of ‘somatics’) referred to this as sensorimotor amnesia. Like the opposite of muscle memory, we forget the huge array of options we have for moving, and rely on the same small set of movement patterns, which contributes to persistent tension.

Other maps of internal experience I like include Asanga’s Elephant Path of Concentration, Jeff Liebermann’s Mediocre Map of Human Experience.